The Museo Jardin del Agua & Carcamo de Dolores

Beyond the promise of Diego Rivera murals, I couldn’t find much info on Mexico City’s Water Garden Museum when deciding whether or not to visit. I’m so glad I took the chance, though, because it’s a gem that doesn’t get high enough billing in lists of Mexico City attractions.

First off, while the two are side by side in Chapultepec Park, when people refer to the Water Garden Museum (Museo Jardin del Agua) they’re often talking about two separate things:

The museum with the Diego Rivera murals is a small hydraulic structure called the Carcamo de Dolores, which charges an entrance fee (just 26 pesos).

Next to that is the real “water garden”, an extensive garden with fountains built around hidden reservoirs. This section is part of the park and free to everyone.

The Water Station Adorned with Diego Rivera Murals

In the 1940s, Mexico City began an ambitious project to bring water into the city from the Lerma River. This water system, of which the Carcamo de Dolores is part, is known as the Lerma System, and still supplies a small percentage of Mexico City’s water.

The Carcamo de Dolores was designed by architect Ricardo Rivas, in collaboration with Diego Rivera, who among other contributions painted the murals inside, and designed the Tlaloc fountain outside. The building was designed as a monument to, and a space to contemplate water, as much as it was a functioning hydraulic water station.

The building opened in 1951, and as it was a fully functioning part of the water system, Rivera’s murals were partially submerged.

As you’d expect, the murals were damaged by exposure to water, and by the time water was diverted away from the Carcamo de Dolores in 1990, significant restoration work was necessary. The floor in particular was very faded, and had to be recreated based on original sketches and documentation, along with the faints lines that remained. The Carcamo de Dolores re-opened to the public in 2010.

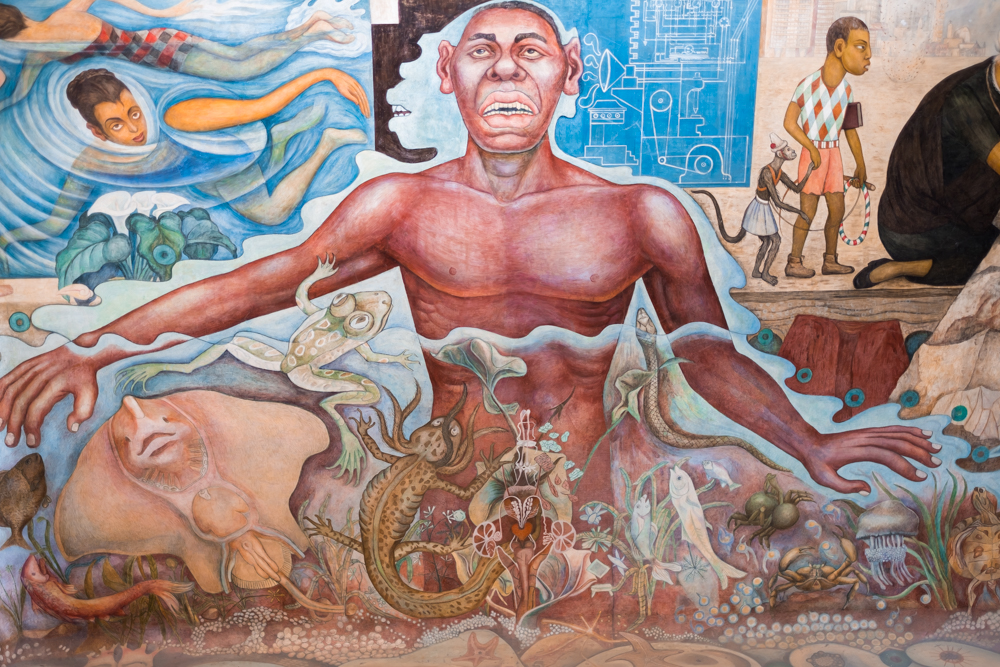

The floor is incredibly detailed, showing the progression from single-celled lifeforms towards the ascension of human beings. The black circle represents both the cellular origins of life and the function of cells themselves. Radiating away from the center are branches of family tree of life. You can see simple organisms like bacteria and amoeba, and more complex animals such as annelid worms and starfish on the right of the floor.

Moving up from the floor, the mural shows the evolution of life, leading to early Homo Sapiens, represented by an African man and Asian woman, reflecting theories of Africa or Asia as the cradle of life.

Moving higher, you see the uses of water represented; agriculture, hygiene and pleasure.

Above the gates is a tribute to the workers and engineers of the water system, in keeping with Rivera’s trademark usage of socialist elements. Below the workers are symbols for the chemicals involved in the purification of water.

The building was originally designed to amplify the sound of the water passing through it. When the flow of water was diverted in 1990, that sound ceased, so Mexican artist Ariel Guzik created the Lambdoma Chamber to preserve the aural experience of the space. To be honest, I don’t entirely understand all the details of how the installation works, but let’s just take a moment to appreciate the fantastic art deco control box below:

Diego Rivera’s Tlaloc Fountain

Also designed by Diego Rivera is a sculpture of Tlaloc, the god of water in Aztec religion, who lies partially submerged in the fountain in front of the Carcamo de Dolores. As with the murals, the fountain had been damaged over the years, though more seriously. A spokesman for one of the organizations involved in the restoration of the Carcamo de Dolores described the fountain as “completely destroyed”, so what exists in the space nowadays may be more re-creation than restoration.

The sculpture is designed to be seen from above. While it’s not the intended bird’s eye view, the steps just beyond the fountain provide a higher vantage point for viewing. Tlaloc has two faces, one looking up at the sky, and the other that you see above, facing the Carcamo de Dolores. I didn’t get a photo that illustrated it, but if you’re standing inside the building facing the sculpture, the face of Tlaloc lines up with the hands in the mural above the tunnel. In this way, the sculpture interacts with the mural, presenting Tlaloc as the giver of water.

The “water garden” next to the Carcamo de Dolores is lovely, but it wasn’t immediately clear to me that it served more than a decorative purpose. Turns out these beautiful raised gardens hide underground reservoirs that were part of the Lerma water system. And those strange towers? They’re disguised pumping stations.

The fountains were sadly dry when we visited, and based on other posts I’ve seen, it seems that the fountains no longer run.

Visiting the Water Garden Museum

While the museum isn’t too difficult to find once you’re in the second section of Chapultepec Park, it seems like the official address won’t take you directly to it.

This may be because the path in front of the Carcamo de Dolores is blocked off and reserved for pedestrians (though you could certainly try to ask your Uber driver to take you to Carcamo de Dolores, and you might end up closer than we did).

When I typed Museo Jardin del Agua into my Uber app to get there, we ended up in front of the building you see above, and were a bit confused. It is part of the original water system, but it was locked, and at any rate, it’s not where the murals are. If you find yourself here, walk past the building and up the hill to get to the gardens, and you’ll find the Carcamo de Dolores on the other side of the gardens.

The gardens are free, and admission for the Carcamo de Dolores is currently 26 pesos.

The Carcamo de Dolores is open Tuesday-Sunday 10am-5pm.