The Meguro Parasitological Museum

Billed as the world’s only museum focused solely on parasites, the Meguro Parasitological Museum in Tokyo is the brainchild of a Japanese doctor who saw a huge uptick in parasite infected patients due to poor sanitation in the wake of World War II. It aims to promote research and educate the public on parasites; however I have a feeling most of its visitors come for the gross out factor. We made sure to fit in a visit for just that reason!

The museum is located on two narrow floors of an unassuming office building– not enough room to display all 60,000 specimens in their collection, but there’s still plenty to look at.

This horror movie prop parasite specimen is, so far as I can gather, a whale’s kidney infected by the nematode Crassicauda giliakiana.

Another type of nematode, Ascaris lumbricoides, is estimated to have infected 70% of the Japanese population due to poor sanitation and scarcity of safe food as the country struggled to rebuild after World War II. While infection symptoms are often minor, I don’t recommend Googling for photos. Or maybe that’s your thing.

My darling boyfriend–who has a background in biology–helped out with the research, then proceeded to Google every disgusting parasite he could think of (not the ones I asked about, but thanks honey) in order to show me the horror-movie photos.

Below, a display showing the life cycle of some of the preserved specimens.

What you’re looking at in the left jar is Schistosoma japonicum in the blood vessels that connect the liver to the small intestine.

This parasite matures in the liver before laying eggs that continue through the intestines or urinary tract to be either passed (and thus potentially infect another host), or circulated back to the liver. Schistosoma worms infect individuals who come into contact with unclean water.

The resulting disease, Schistosomiasis, kills somewhere between 12,000-200,000 people a year, underscoring the need for clean water in developing countries. S. japonicum was largely eradicated in Japan after the government encouraged a move away from using water oxen for farming, as they can pass on the parasite.

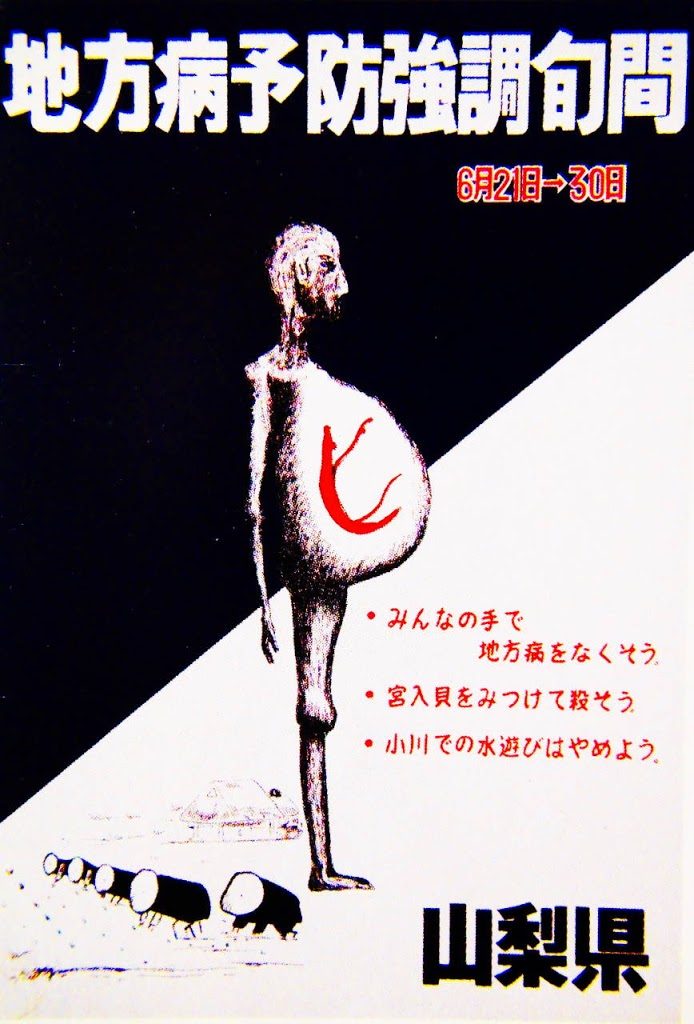

Below, a creepy 1971 Japanese educational poster for Schistosomiasis. The characteristic distended stomach is caused by liver damage from the Schistosoma eggs, which then results in abdominal swelling.

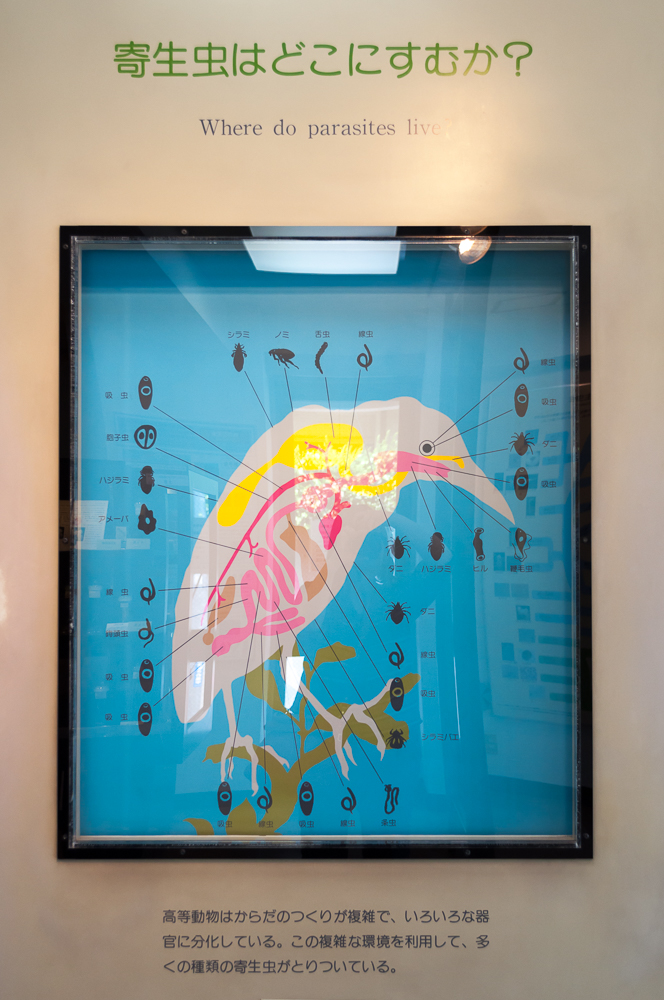

It’s a wonder this poor bird is still standing (dammit, where’s an ex-parrot joke when I need one?), as he appears to be completely riddled with parasites. Really, they’re showing parasites and the organs they can infect.

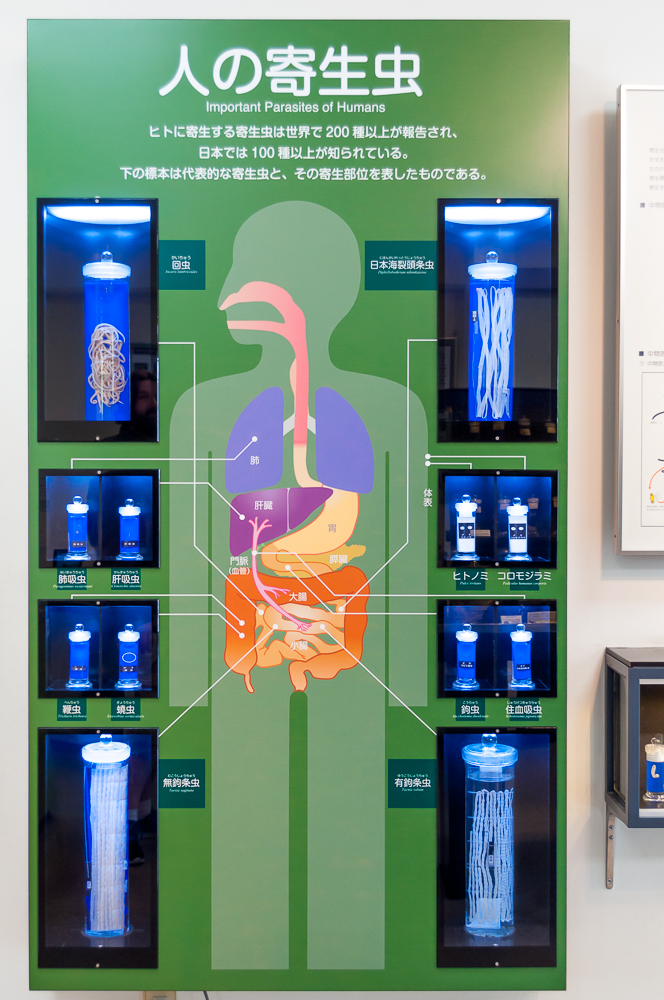

If you’re already afraid of what’s in your food, don’t head up to the second floor, which explores human parasites:

A nearly 30 foot tapeworm! If you need a clearer illustration of just how long this is, grab the end of the ribbon hanging next to it and stroll across the room. This particular tapeworm is the Diphyllobothrium nihonkaiense, which unsurprisingly infects humans who munch on raw or undercooked fish.

But don’t put down your sushi! Infection from sushi is relatively rare because the risk stems mainly from freshwater fish which are rarely used in sushi. This may be why the museum booklet describes D. nihonkaiense as stemming from the consumption of raw trout.

Raw salmon is easily my favorite, and has a fascinating history. Because of the possibility of parasites in a fish which migrates between fresh and salt water, salmon has only recently become a sushi bar staple in Japan.

When Japanese overfishing created a potential market for Norwegian fish in Japan, Norway took advantage of the opportunity by launching a concerted PR campaign on behalf of Norwegian salmon in the 1980s. While the Norwegian article doesn’t address how the parasite concerns were resolved, apparently Japan’s indigenous Ainu population had long been freezing salmon to kill parasites, and this same basic technique of deep freezing is employed in much of Japan and the US today to ensure the fish is safe to eat.

“Important Parasites of Humans”, showing the organs they infect. Amongst the creepy crawlies are our friends Ascaris lumbricoides, Schistosoma japonicum, a Chinese liver fluke, and beef and pork tapeworms.

Above, wax casts of parasite eggs 1,000 times the actual size. These were created as a teaching tool by Jinkichi Numata, a technician at the Institute for Infectious Disease.

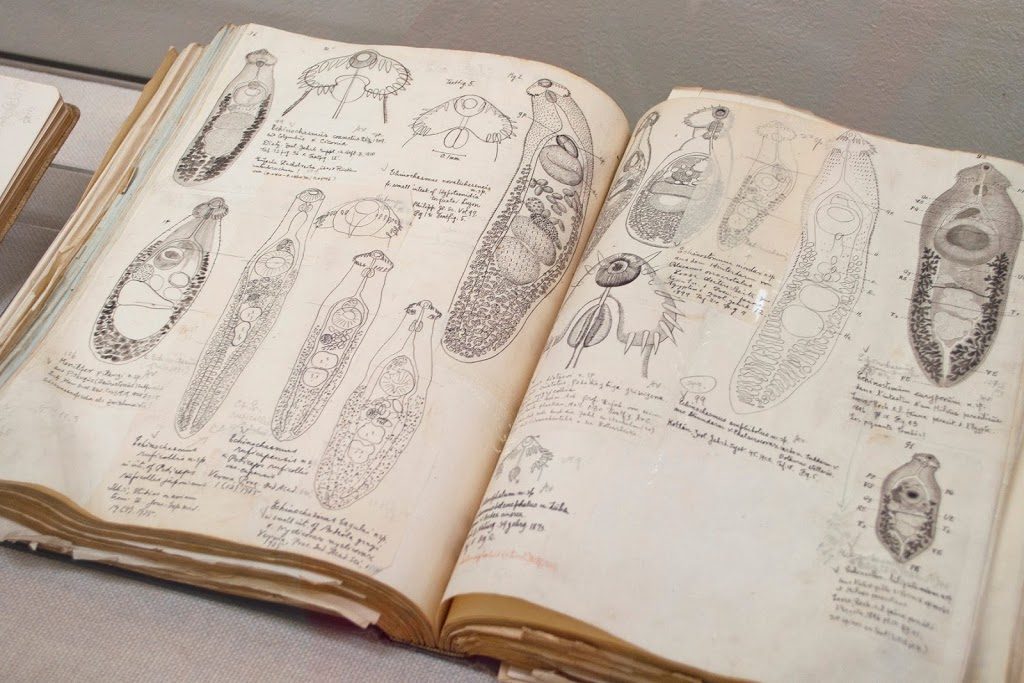

The beautifully detailed sketches below are just one of the books on display from Dr. Stayu Yamaguti, who contributed substantially to parasite research. These sketches and notes were not entirely his own observations, rather they were his way of compiling current research and theories.

The small gift shop on the second floor. They offer postcards, tote bags, t-shirts and some smaller items, but I can’t help feel that they’re missing out on the market for over-the-top merchandise many tourists would buy. Still, there’s a couple pretty gross postcards if you’d like to horrify your friends back home.

After all this, you’d think food would be the last thing on our minds, but we were starving and headed across the street for some excellent takoyaki.

Yum!

Visiting the Meguro Parasitological Museum:

-Admission is free and the museum is open Tuesday through Sunday 10-5

-The museum is approx 15 minute walk from Meguro station, check out their website for detailed directions, or use Google maps–which served us quite well for most of our city destinations in Japan.

Related posts:

The Ramen Amusement Park in Yokohama

Where to buy sold out Ghibli Museum Tickets